Deep-sea vents

Highly reduced and thermally charged venting fluids from the subseafloor mix with surrounding seawater, creating a sharp geochemical gradient which promotes a hub of biological diversity at the site of venting fluid. Studies of the bacterial and archaeal chemosynthetic populations at hydrothermal vent sites have highlighted the important roles these microorganisms play in deep-sea carbon cycling and offered a unique window into subseafloor microbiology. To date, studies of deep-sea food webs and ecological interactions do not typically cover the microbial eukaryotic assemblages.

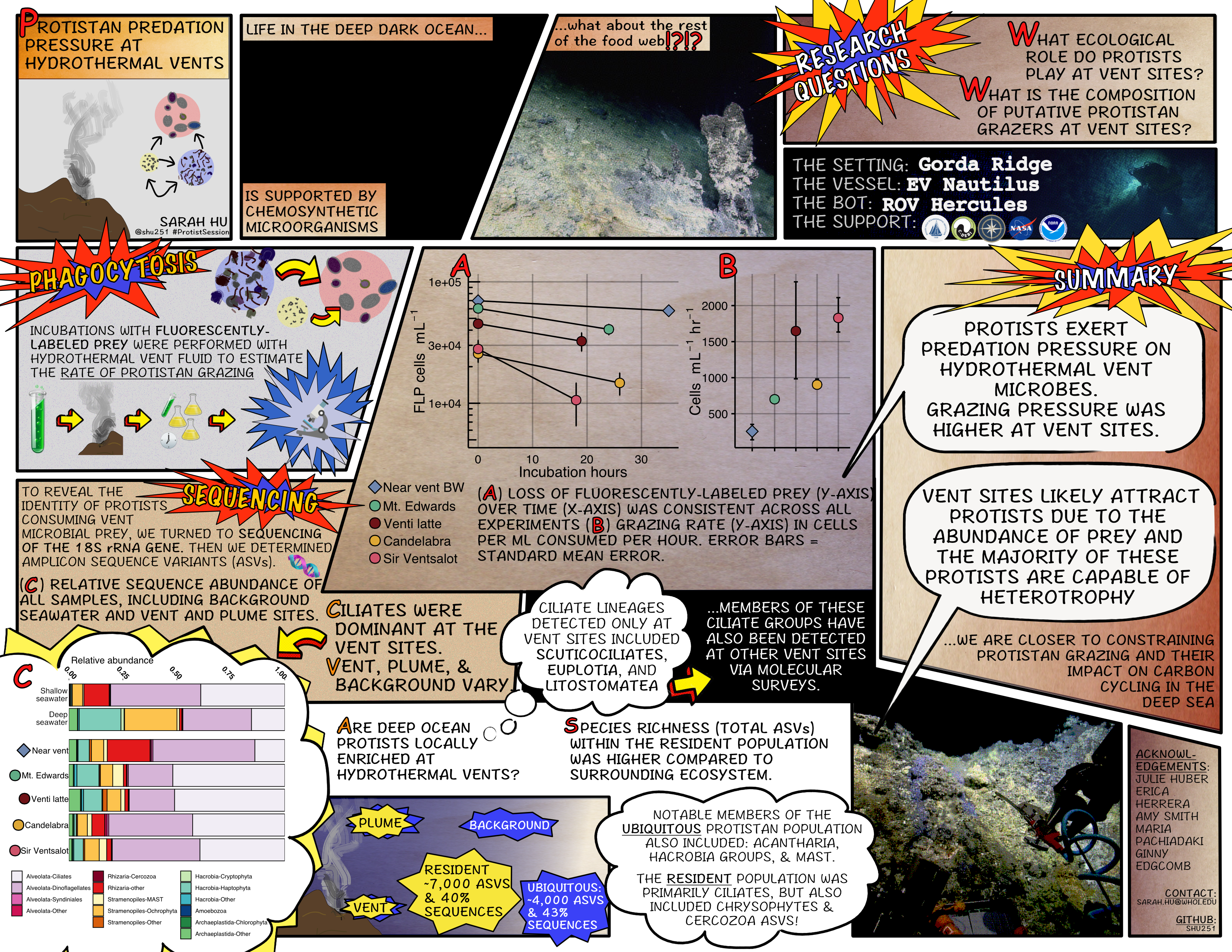

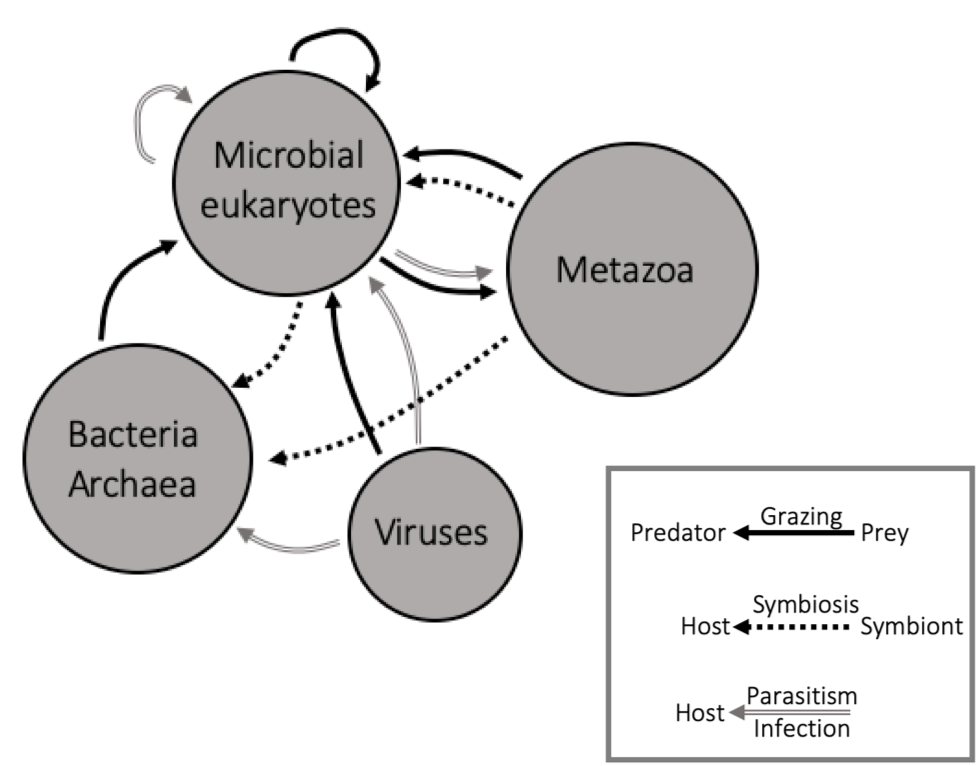

Heterotrophic protists are ubiquitous in all aquatic ecosystems and represent an important ecological link by transferring organic carbon from primary producers to higher trophic levels. Previous work has shown protists to be present and active at deep-sea hydrothermal vents and efforts to characterize the composition of these populations has revealed many species to be heterotrophic grazers and parasites. However, efforts to quantify protistan grazing pressure in the deep sea are rare.

1 Questions

Supported by the Center for Dark Energy Biosphere Investigations STC, I joined Dr. Julie Huber’s lab at WHOI. Since 2018, I have been involved in several expeditions to hydrothermal vents (see below) to address these main questions:

What is the role of protists in deep-sea hydrothermal vent food web ecology?

How does protistan diversity, distribution, and activity influence carbon flux in the deep sea?

What is the biogeography and distribution of the deep-sea hydrothermal vent microbial eukaryotic community?

What biotic or abiotic parameters appear to influence protistan community diversity at deep-sea hydrothermal vents?

2 Accessing deep-sea food webs

To assess microbial biodiversity, we rely on sequencing the DNA from microbial cells that are collected onto a filter. The genetic material is extracted and sequenced so we can gain a snapshot of the microbial community composition (who is present?). These molecular approaches have been critical in gaining the knowledge we currently have on the microbial communities in deep-sea and difficult to range habitats. Actually getting to deep-sea habitats takes a lot of engineering and planning. Broadly, we can use remotely- or human-operated vehicles (ROVs and HOVs) from a ship. Often we have to run experiments on the ship once the ROV returns with hydrothermal vent fluid or have the ROV collect samples in situ.

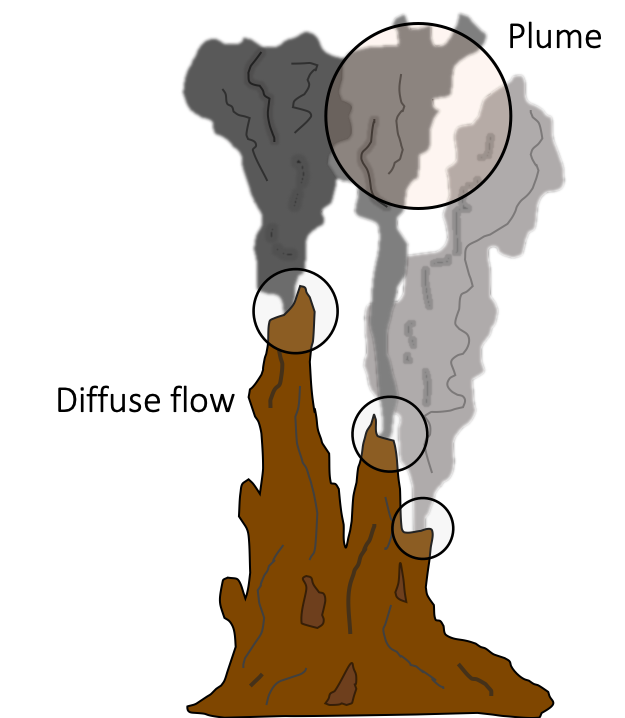

For this work, I run incubations with diffuse flow fluid collected via ROV to capture the grazing activity of heterotrophic protists. Consumption of microbial prey by protistan grazers (heterotrophs) is a key route of carbon exchange (the transfer of chemosynthetic microorganisms to higher trophic level), and these experiments allow us to obtain a grazing rate (cells consumed ml^-1 day ^day). In order to assess the level of grazing pressure by protists, I compare and contrast the grazing rates and community composisions of protistan assemblages within discharging vent fluid, the plume (hydrothermally-influenced environment above the vent site), and the background deep-sea water.

Protistan grazing is higher within diffuse vent fluid

In aquatic habitats, transition zones driven by changes in chemistry or nutrients can create biological ‘hotspots’ of microbial activity. Within the hydrothermal vent environment

3 Deep-sea vent protists

We conducted an 18S rRNA gene survey to see how distinct microbial eukaryotic populations were within vent fluids situated meters apart compared to oceans apart.

The total number of protistan species detected with amplicon sequencing was consistently higher within diffusly venting fluid at each vent site (compared to the plume and background environment). Few species appeared to be shared across vent fields, and populations at individual vent sites (only meters apart) were largely distinct from one another.

Protistan diversity is elevated within diffuse vent fluid

4 Microbes need frenemies

Can the interaction of microbes with others be defined as friendly? rival? or frenemy?

Ecological interactions among microbes (bacteria and archaea), viruses, and eukaryotic microorganisms are critical junctions in marine food webs. These interactions range from mutually beneficial relationships to sources of microbial mortality. Interactions between viruses-microbes and eukaryotes-microbes at deep-sea hydrothermal vents impact local carbon cycling. This project aims to identify these microbial interactions, specifically those related to cell death by protistan grazing or viral lysis, and explore how they vary across different hydrothermal vent habitats. By providing a better understanding of the composition and nature of these relationships, the investigators aim to build a better food web model of deep-sea hydrothermal vents and improve our understanding of how climate change and other human activities impact the ecosystem.

Outcomes from this project include the generation of new microbiology, oceanography, and computer science curricula targeted at community college students. In addition, it involves research with undergraduate students at all stages of the research process and provides opportunities for professional development and peer-to-peer mentoring.

5 Field work

5.1 Axial Seamount 2022 & 2023

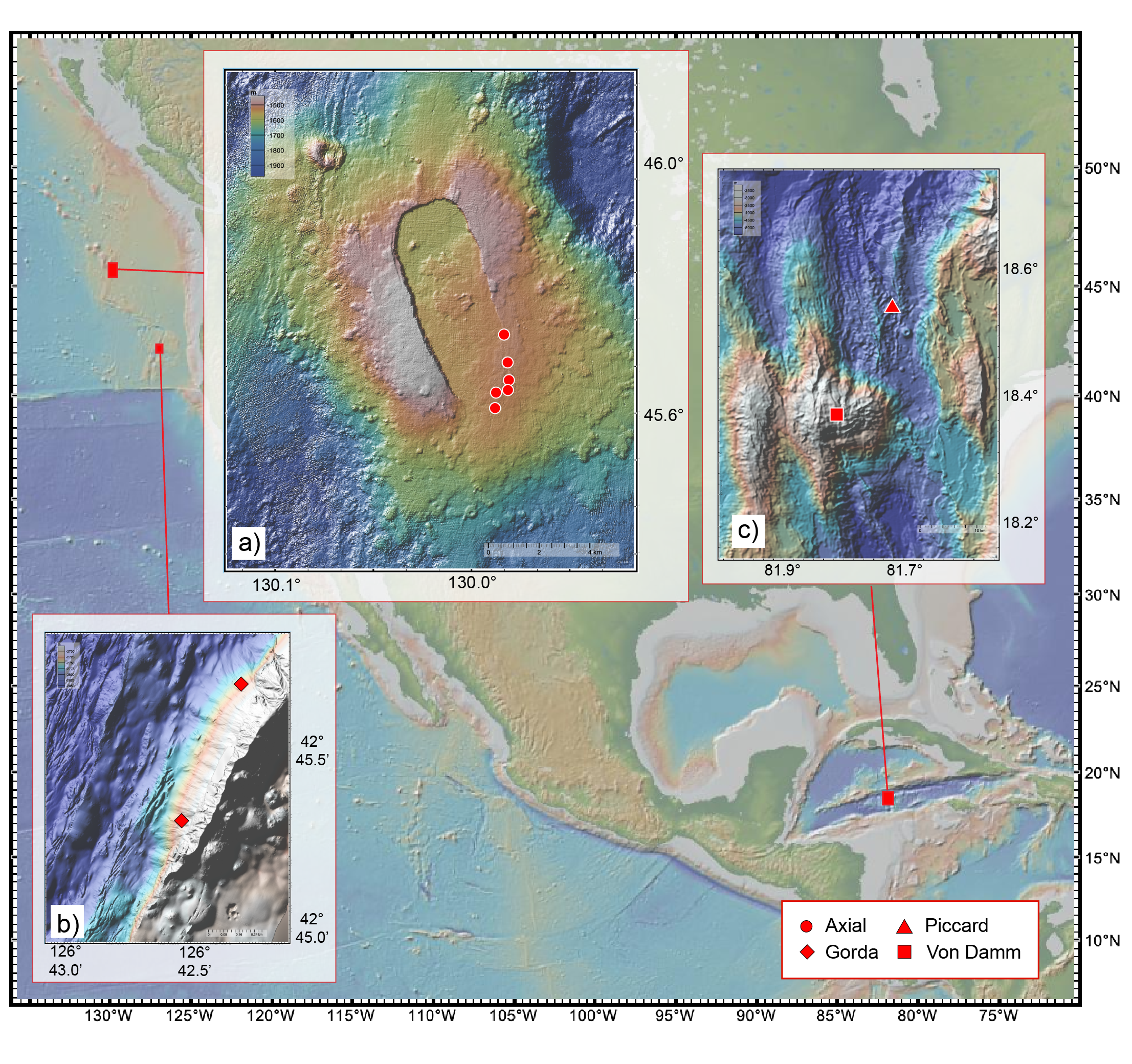

We visited Axial Seamount (NE Pacific Ocean) in both 2022 and 2023 as part of an NSF-funded proposal to characterize the rate and route of carbon via phagotrophic protists.

Read more about our expedition from our cruise blog

Axial Seamount is an active submarine volcano on the Juan de Fuca Ridge in the NE Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Oregon. The microbiome of the low-temperature (<100C) diffuse vent sites in the region have been frequently studied and the vent field within the caldera include a range of distinct geochemistries.

PhD students Kayla Nedd & Alexis Adams were featured on the National Deep Submergence Facility cruise blog.

5.2 Mid-Cayman Rise - 2020 Expedition

I was a part of the RV Atlantis (AT42-22) research cruise to study the geochemistry and microbiology of the Von Damm and Piccard vent fields, located on the Mid-Cayman Rise. We completed 9 dives with ROV Jason at the Von Damm and Piccard vent fields. Hydrothermal vent fluid collection was facilitated by the isobaric gas-tight (IGT) fluid samplers (9) and the hydrothermal organic geochemistry (HOG) sampler (Susan Lang). CTD-rosette casts were also conducted to obtain water column plume and background seawater. Relevant objectives included (1) conducting grazing incubations and (2) collecting samples from the hydrothermal vent, plume, and background seawater environments. Laboratory work for analyzing the grazing experiments and cell counts has been completed and the molecular work is in progress.

Samples from Von Damm (10 sites) and Piccard (8 sites) vent fields will provide detailed analysis of the microbial composition, biogeography, and role in the food web. 3 of the grazing experiments originated from CTD-rosette casts from the background and plume environment and 6 were conducted with fluid from the HOG. 4 grazing experiments were performed with the IGT, so incubations remained at in situ pressure.

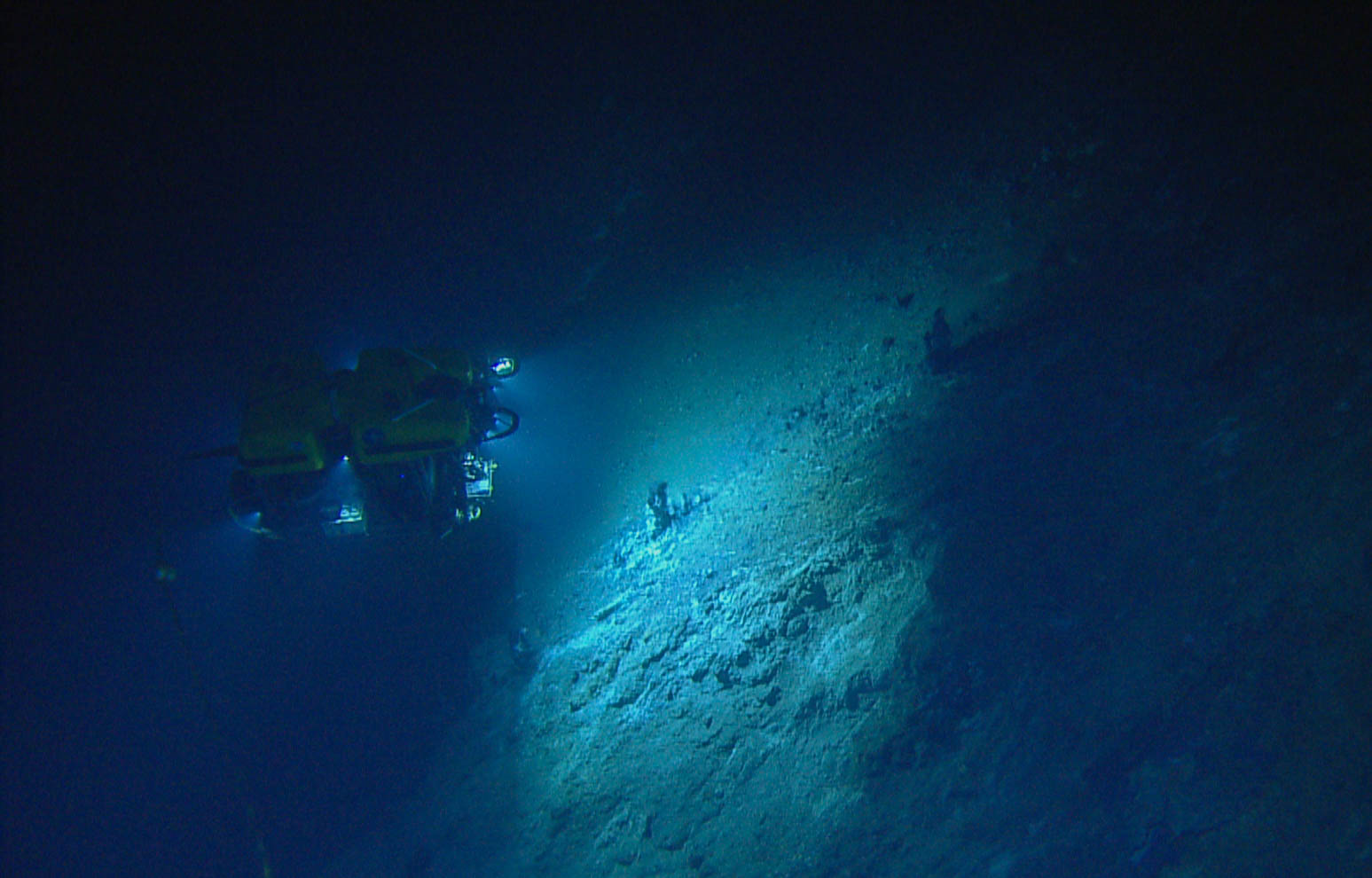

{fig.cap=“ROV Hercules at newly discovered Apollo vent field. Credit: OET/Nautilus Live”}

{fig.cap=“ROV Hercules at newly discovered Apollo vent field. Credit: OET/Nautilus Live”}

5.3 Gorda Ridge - 2019 Expedition

Sea Cliff and Apollo vent fields along the Gorda Ridge spreading center, located ~200 km off the coast of southern Oregon, were visited in May-June 2019 with the E/V Nautilus (cruise NA108; 5). Low temperature diffuse hydrothermal vent fluid samples <100ºC were collected using the ROV Hercules and a SUspended Particle Rosette Sampler (SUPR; 6). The overarching goal of the cruise was to integrate scientific investigation of the deep sea with the exploration of ocean worlds on other planets, as the deep-sea hydrothermal vent system serves as an analog environment (a part of the SUBSEA program (Systematic Underwater Biogeochemical Science and Exploration Analog)).

Findings from the Gorda Ridge cruise are published: Hu, S.K., Herrera, E.L., Smith, A.R., Pachiadaki, M.G., Edgcomb, V.P., Sylva, S.P., Chan E.W., Seewald, J.S., German, C.R., & Huber, J.A. (2021) Protistan grazing impacts microbial communities and carbon cycling in the deep-sea hydrothermal vent environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA link code

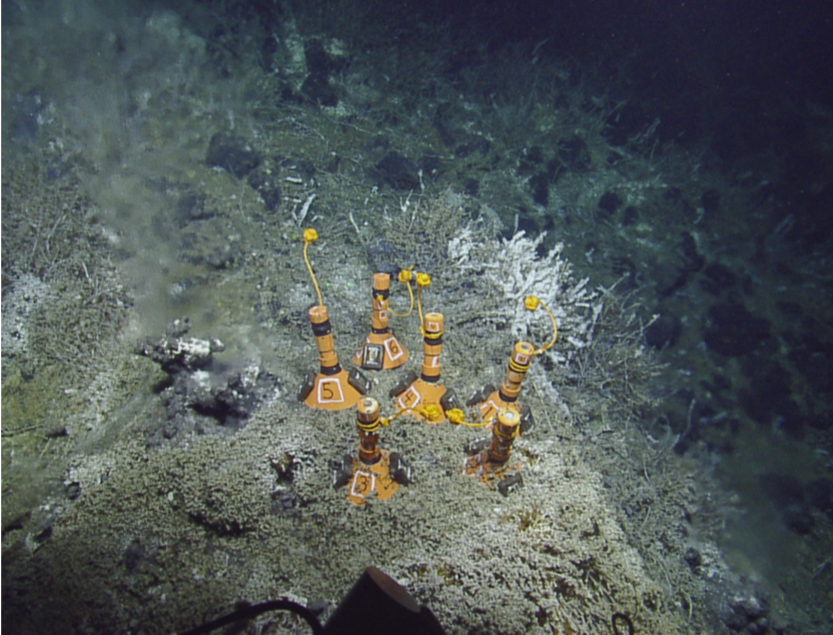

All 6 microcolonizer experiments (pictured above) were placed on and near active diffuse flow at Mt. Edwards, each had substrates that included: shell (CaCO3) Riftia tubeworm shell (chitin), quartz, pyrite, basalt, and olivine). Microcolonizers experienced a range of temperatures, influenced by the diffusely venting fluid nearby

What species colonize these substrates first?

Does species richness and evenness vary by substrate type?

Are the same species found on the substrates also found at the diffuse vent fluid?

A summary of my findings were presented as part of the ISOP virtual poster session.